Overview

The work of Joshua Makeover, MD, in defining medical device innovation has accelerated the development of new technologies and the formation of startup companies.

Products developed by Stanford Biodesign graduates have been used to help more than 10 million people

Joshua Makower, MD, may be one of the most influential people in the field of medical device innovation. Makower’s work on defining medical device innovation has accelerated the development of new technologies and the formation of startup companies. Currently, Makower is the Yock Family Professor of Medicine and Bioengineering at the Stanford University Schools of Medicine and Engineering. He is also the Director of the Stanford Byers Center for Biodesign, which he has led since 2021.

In 2001, Makower cofounded the Biodesign program with interventional cardiologist Paul Yock, MD, on the premise that the process of innovation can be taught. Their principles underlying innovation rest on systemically defining the clinical need, invention of the solution, and creation of a business model or research proposal that has the potential to demonstrate commercial success. Over the years its approach has been emulated at more than 50 universities globally to train students, and it has spawned a new generation of health tech entrepreneurs who are addressing major clinical gaps.

Makower estimates that products developed by Stanford Biodesign graduates have been used to help more than 10 million people, and that the Stanford program alone has produced 56 companies. Biodesign’s formation gained greater acceptance following the 2009 publication of the 1,000-page textbook he co-authored on the subject titled Biodesign: The Process of Innovating Medical Technologies.

If there is one takeaway from Makower’s work, it is that medical device innovation is a process that can be learned, and that innovation does not originate from unpredictable lightning-strike moments experienced by geniuses. “Innovation is a mysterious thing until you break it out into individual steps, and then it is very doable by anyone,” he says.

Innovation as a Process

Long before he was teaching others how to innovate, Makower was a graduate from NYU School of Medicine who immediately went into industry. During a stint at Pfizer, he was tasked with determining why the company’s $2 billion medical device business was stifling innovation acquired from external sources. His findings convinced him that big companies drove decisions based on their technologies, rather than on carefully nuanced needs-based assessments of gaps in clinical care. He founded an incubator within Pfizer based on these principles. Then, in 1995, he left to start his own incubator called ExploraMed.

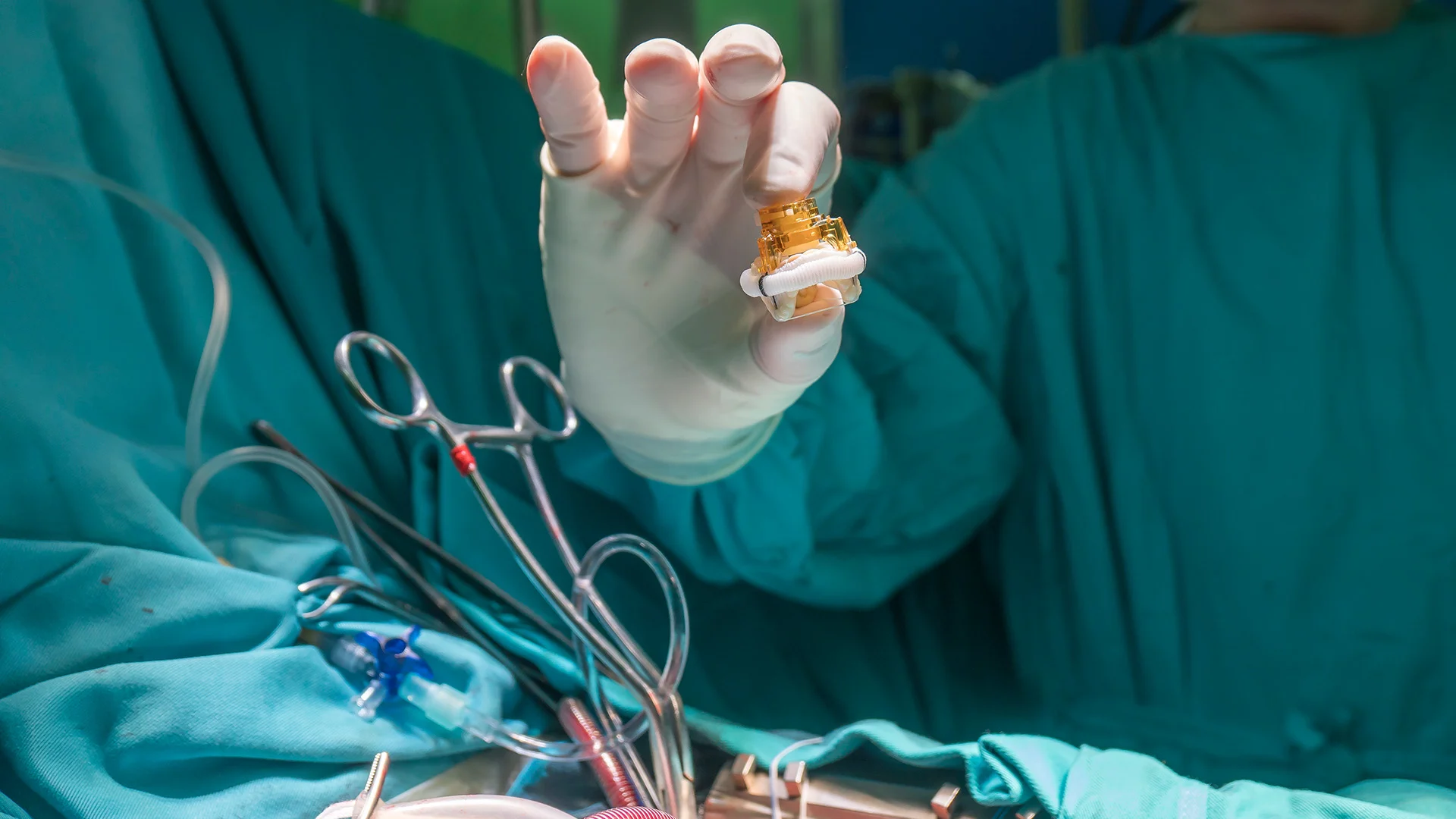

Since then, ExploraMed has spawned a slew of successful medical device startups, including TransVascular (a catheter-based drug delivery system acquired by Medtronic in 2003 for an undisclosed sum), Acclarent (an ENT company acquired by Johnson & Johnson in 2010 for $785 million), and NeoTract (a urology company acquired by Teleflex in 2017 for $1.1 Billion). Makower also advises some of the world’s best known venture capital firms and sits on the boards of a handful of small medical device companies.

After Acclarent was sold, Makower decided to focus on a new issue: overhauling cumbersome FDA regulations that were delaying approvals of medical devices, adding cost and time for companies, and impacting patient care.

In 2010, a study he led presented data for the first time detailing how FDA’s opaque and unpredictable review processes had significant financial and clinical impact on patients. That study helped pave the way for Congress to pass The Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act of 2012, which reformed deadlines, regulatory processes and requirements for medical device approvals.

Next Up: Reforming Reimbursement

More recently, Makower has aimed at the reimbursement system for medical devices, which he says is now the biggest challenge for those involved in new technology creation and adoption.

Innovating has become hugely difficult because companies are struggling to get their technologies paid for, he says, yet many of these technologies will ultimately save the healthcare system money by helping patients use it less. Because navigating the current system and its delays is expensive, companies are charging more for their products to return money to investors. A more transparent, predictable and faster reimbursement process would appeal to investors and allow medtech startups to generate returns sooner, which means less capital would be required to keep them running during the development process. In addition, needed therapies would get to patients sooner.

Makower is applying the same strategy he used on the FDA in 2010 to change the reimbursement landscape. A study he led on the length of time between FDA authorization of a novel technology and Medicare coverage of it was published in JAMA Health Forum on August 4, 2023 based on findings for 64 novel technologies. It found that the median time to at least nominal coverage for the cohort was 5.7 years. The study concluded that “existing coverage processes may affect timely reimbursement of new technologies.”

Makower has a bucket list of potential reforms, but the hottest item on the agenda these days is CMS’ proposed TCET pathway for reimbursement (Transitional Coverage for Emerging Technologies). The proposal was put forth in June 2023 to create a streamlined framework for national coverage of new devices. Still, it doesn’t go as far as many device advocates had hoped, leaving industry to wait for a final guidance that has yet to be published.

While TCET is certainly a meaningful improvement upon the current process, there is some hope that a new bi-partisan bill, “Ensuring Patient Access to Critical Breakthrough Products Act of 2023” (H.R. 1691), will move forward and be signed into law. If this happens, a broader positive impact on patient care and the healthcare innovation ecosystem could be realized, Makower says.

Given spiraling healthcare costs and tight government budgets, the task seems daunting. But Makower is up to the challenge. “People doubted in 2010 that we could solve the FDA challenges we were having, and we did,” he said. “So I believe we can solve these reimbursement challenges as well, but we need to approach it with all stakeholders in mind – especially patients – and although it is likely to be a multi-year process, I think this is a challenge we can rise to as well.”